Pôle Bocage

et Faune Sauvage

-

Bocage and hedgerows in France

According to the summary produced by Jean-Christophe Tourneur and Stéphane Marchandeau (ONCFS, 1996)

The term bocage refers to a type of rural landscape resulting from a combination of changes in the natural environment and in rural society.

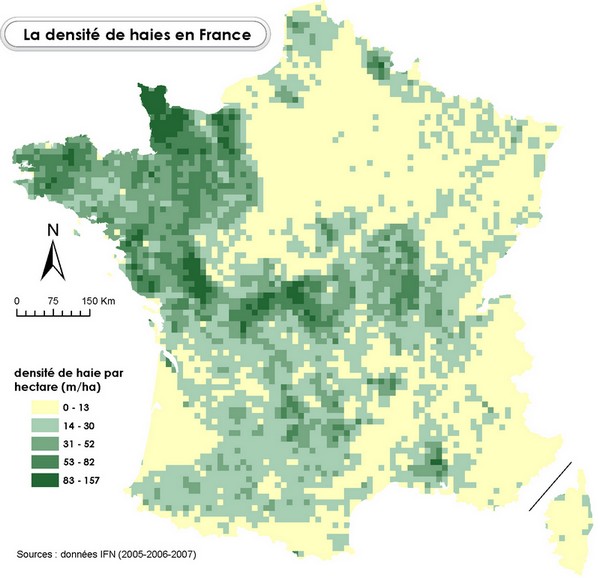

The term bocage refers to a type of rural landscape resulting from a combination of changes in the natural environment and in rural society. This typical Western European terrain, which in France is especially prevalent in the western Armorica, western Vendée, Limousin, Bourbonnais, Thiérache and Pays Basque regions, is almost directly opposed to the open-field landscapes of eastern France, Rhineland and eastern Germany, and certain parts of eastern Europe.

This typical Western European terrain, which in France is especially prevalent in the western Armorica, western Vendée, Limousin, Bourbonnais, Thiérache and Pays Basque regions, is almost directly opposed to the open-field landscapes of eastern France, Rhineland and eastern Germany, and certain parts of eastern Europe.

Although bocage is a long-established feature of our countryside, and may have existed since the iron age, it became much more widespread starting in the 18th century, when strong population growth combined with the breaking up of properties previously owned by the nobility led to the subdivision of communal land and large estates (Flatres, 1976 - Meynier, 1976).

Although bocage is a long-established feature of our countryside, and may have existed since the iron age, it became much more widespread starting in the 18th century, when strong population growth combined with the breaking up of properties previously owned by the nobility led to the subdivision of communal land and large estates (Flatres, 1976 - Meynier, 1976).

Meynier, in 1976, defined bocage as "a lush, enclosed landscape". Although surprisingly simple, this definition is universally accepted by geographers and ecologists. Strictly speaking, bocage environments feature a network of hedgerows forming a patchwork of variable size and geometry, and they consist of or are bounded by a strip of vegetation - live hedges in most but not all cases Flatres, (1976 and 1993 –Mondolfo & Lorfeuvre, 1986, inter alia).

Meynier, in 1976, defined bocage as "a lush, enclosed landscape". Although surprisingly simple, this definition is universally accepted by geographers and ecologists. Strictly speaking, bocage environments feature a network of hedgerows forming a patchwork of variable size and geometry, and they consist of or are bounded by a strip of vegetation - live hedges in most but not all cases Flatres, (1976 and 1993 –Mondolfo & Lorfeuvre, 1986, inter alia). There are many variations on this basic theme, ranging from bocage fields in the Massif Central that are enclosed by hedges but no earth banks to the dense networks of small hedged fields found in parts of Basse-Normandie.

There are many variations on this basic theme, ranging from bocage fields in the Massif Central that are enclosed by hedges but no earth banks to the dense networks of small hedged fields found in parts of Basse-Normandie. There are many subcategories, depending on the type of land and the type of enclosure, the dominant tree species, the shape and scale of the field patchwork and the origins of the bocage. According to the latter criterion, there are three basic types (Soltner, 1986 & 1991, inter alia): secondary bocage, semi-bocage and degraded bocage. Numerous authors (Baudry and Burel, 1985 - Burel, 1990 - Coutel, 1992, inter alia) have emphasised the importance of not considering merely the field pattern, but also the structure of the hedgerows that define it. They stress the heterogeneous nature of the bocage network, which is apparent in both the spatial distribution and individual composition of hedgerows, while historical factors have influenced their distribution density.

There are many subcategories, depending on the type of land and the type of enclosure, the dominant tree species, the shape and scale of the field patchwork and the origins of the bocage. According to the latter criterion, there are three basic types (Soltner, 1986 & 1991, inter alia): secondary bocage, semi-bocage and degraded bocage. Numerous authors (Baudry and Burel, 1985 - Burel, 1990 - Coutel, 1992, inter alia) have emphasised the importance of not considering merely the field pattern, but also the structure of the hedgerows that define it. They stress the heterogeneous nature of the bocage network, which is apparent in both the spatial distribution and individual composition of hedgerows, while historical factors have influenced their distribution density. Other features typical of bocage landscapes include a wide variety of plant life, particularly in the hedgerows but also among crops, specific climate conditions and interpenetrating farmed and non-farmed areas. Mixed-crop and livestock farming are traditional in bocage areas, where permanent meadows are found alongside feedstuff, grain and row crops.

Other features typical of bocage landscapes include a wide variety of plant life, particularly in the hedgerows but also among crops, specific climate conditions and interpenetrating farmed and non-farmed areas. Mixed-crop and livestock farming are traditional in bocage areas, where permanent meadows are found alongside feedstuff, grain and row crops. -

Role of hedgerows

According to the summary produced by Tourneur et Marchandeau (ONCFS, 1996) :

According to the summary produced by Tourneur et Marchandeau (ONCFS, 1996) : The benefits of hedges and earth banks are well known (Chemin, 1975 – Lucas, 1965 – Soltner, 1986 and 1991, inter alia). Many authors have already described the consequences of over-zealous hedge uprooting. Hedgerows perform the following key functions (identified by Le Duc and Terrason (1974, inter alia) :

The benefits of hedges and earth banks are well known (Chemin, 1975 – Lucas, 1965 – Soltner, 1986 and 1991, inter alia). Many authors have already described the consequences of over-zealous hedge uprooting. Hedgerows perform the following key functions (identified by Le Duc and Terrason (1974, inter alia) :

Regulate the micro-climate

Regulate the micro-climate

Regulate water movements

Regulate water movements

Preserve the soil

Preserve the soil

Maintain the balance of species

Maintain the balance of species

Production

Production

Enhance the local lifestyle

Enhance the local lifestyle Their main roles are perceived differently in different regions. For example, in Brittany they are valued for the protection they afford against strong winds, whereas in the Avesnois region, they are appreciated as a source of wood (Coutel, 1992).

Their main roles are perceived differently in different regions. For example, in Brittany they are valued for the protection they afford against strong winds, whereas in the Avesnois region, they are appreciated as a source of wood (Coutel, 1992). -

Characteristics of bocage with regard to wildlife

According to the overview produced by Tourneur and Marchandeau (ONCFS, 1996) :

Hedgerows consisting of varied species of trees, shrubs and grasses provide the vertebrates that frequent them with :

Hedgerows consisting of varied species of trees, shrubs and grasses provide the vertebrates that frequent them with :

A structure offering varied food sources,

A structure offering varied food sources,

A structure offering varied forms of shelter, in which to reproduce, rest and take refuge from predators or the miscellaneous threats presented by the environment,

A structure offering varied forms of shelter, in which to reproduce, rest and take refuge from predators or the miscellaneous threats presented by the environment,

A linear structure encouraging movement by individual animals (corridors), which may contribute to the survival of populations organised as meta-populations (Burel, 1990 – 1984 – Lodé, 1991A – Paillet & Butet, 1994 6 Saint-Girons et al. 1986),

A linear structure encouraging movement by individual animals (corridors), which may contribute to the survival of populations organised as meta-populations (Burel, 1990 – 1984 – Lodé, 1991A – Paillet & Butet, 1994 6 Saint-Girons et al. 1986),

An "edge" area, where hedges and a range of crops interpenetrate over long distances. "Edge effects" (Frochot & Lobreau. 1987), often sought after by wildlife, are characterised by sharp gradients in ecological factors; a wide variety of exchanges take place along the frontier (ecotones) between the two types of terrain. Indeed, a hedgerow itself is a double edge.

An "edge" area, where hedges and a range of crops interpenetrate over long distances. "Edge effects" (Frochot & Lobreau. 1987), often sought after by wildlife, are characterised by sharp gradients in ecological factors; a wide variety of exchanges take place along the frontier (ecotones) between the two types of terrain. Indeed, a hedgerow itself is a double edge.

A hedge provides shelter and food for a host of animals from all zoological groups (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, molluscs, insects, microorganisms, etc.), on all colonisation levels (ground, bed of leaves or humus, foliage, stems, trunks and high branches), and with all forms of feeding (detritivores, herbivores, granivores, insectivores and carnivores). As explained by Saint-Girons (1952), "the key feature of bocage, from a wildlife perspective, is the rarely-found combination of shelter (earth banks covered with dense vegetation and permanent underground burrows) and plentiful reserves of food provided by crops."

A hedge provides shelter and food for a host of animals from all zoological groups (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, molluscs, insects, microorganisms, etc.), on all colonisation levels (ground, bed of leaves or humus, foliage, stems, trunks and high branches), and with all forms of feeding (detritivores, herbivores, granivores, insectivores and carnivores). As explained by Saint-Girons (1952), "the key feature of bocage, from a wildlife perspective, is the rarely-found combination of shelter (earth banks covered with dense vegetation and permanent underground burrows) and plentiful reserves of food provided by crops." However, another significant characteristic of bocage is the absence of wildlife specific to that particular habitat (the same applies to plants); the fact that this agro-ecosystem has emerged only recently has prevented inbreeding. Nevertheless, three features are worthy of note, given that the specificity of this environment derives from their co-existence :

However, another significant characteristic of bocage is the absence of wildlife specific to that particular habitat (the same applies to plants); the fact that this agro-ecosystem has emerged only recently has prevented inbreeding. Nevertheless, three features are worthy of note, given that the specificity of this environment derives from their co-existence :

Species richness, which enables hedges to play an important role in biodiversity :

Species richness, which enables hedges to play an important role in biodiversity :

They are a melting pot for species from a wide variety of biotopes, including woodland, marshes, moors and open fields. This immediately becomes apparent when one considers the variety of habitats found in a bocage landscape, together with its significant edge effects. Nevertheless, hedges may offer good living conditions for a particular species without it actually being present, due to its isolation from sources of propagules;Species diversity :

This is undoubtedly the most obvious characteristic. Numerous species are found here, in most cases without being particularly abundant or particularly rare. This trait is specific to mixed landscapes, in contrast to single-crop, open field-based agrosystems and single-species forests;Balance of species :

This characteristic derives from the previous two, being the result of the interactions between animals. Although cyclical fluctuations in population densities are not unheard of, they rarely occur on the scale observed in other systems. This role is most pronounced where there is the greatest diversity of species, and hence the most complex food chains (as in long-established hedges comprising native species). The hedgerow, situated at the interface between several habitats, is an ideal crossing point, sanctuary and place of exchange for wildlife. In addition, hedges form a connective fabric that facilitates animal movements. Clearly, hedges play a fundamental biological role, and it is easy to demonstrate that the diversity of species living in a hedgerow safeguards not only the hedge’s biological activity (with each animal finding food and shelter) but also its aesthetic appearance. Hedges also influence their environment. This additional role is indissociable from their biological function, whether with regard to the local or regional climate, water resources or the economy (Coutel, 1992 – Gaury, 1987 – Laugley-Danysz, 1984).

Clearly, hedges play a fundamental biological role, and it is easy to demonstrate that the diversity of species living in a hedgerow safeguards not only the hedge’s biological activity (with each animal finding food and shelter) but also its aesthetic appearance. Hedges also influence their environment. This additional role is indissociable from their biological function, whether with regard to the local or regional climate, water resources or the economy (Coutel, 1992 – Gaury, 1987 – Laugley-Danysz, 1984). -

Impact on wildlife of recent changes involving bocage landscapes

According to the overview produced by Tourneur and Marchandeau (ONCFS, 1996) :

Bocage structures are evolving, rapidly in a trend towards simplification due to the destruction of a large numbers of hedges and earth banks, combined with changes in farming systems, which are becoming increasingly intensive and specialised. This hedge removal process depletes biological diversity as a result of :

Bocage structures are evolving, rapidly in a trend towards simplification due to the destruction of a large numbers of hedges and earth banks, combined with changes in farming systems, which are becoming increasingly intensive and specialised. This hedge removal process depletes biological diversity as a result of :

Disappearance of species that, at one stage or another in their development cycle, have make use of this uncultivated area, particularly species such as reptiles that depend on the existence of earth banks for their survival,

Disappearance of species that, at one stage or another in their development cycle, have make use of this uncultivated area, particularly species such as reptiles that depend on the existence of earth banks for their survival,

Development of species well-suited to open fields (such as the starling), which can be considered "harmful" to insect-eating birds, for example, causing them to become scarce due to decreased availability of crop-dwelling insects.

Development of species well-suited to open fields (such as the starling), which can be considered "harmful" to insect-eating birds, for example, causing them to become scarce due to decreased availability of crop-dwelling insects. Saint-Girons (1993) explains that "the main effect of the changes to the landscape currently taking place before our eyes is to decrease an area’s diversity, and more rarely its species richness, and to encourage invasive species.

Saint-Girons (1993) explains that "the main effect of the changes to the landscape currently taking place before our eyes is to decrease an area’s diversity, and more rarely its species richness, and to encourage invasive species. Fortunately, a period of land consolidation marked by "hedge clearance on a massive scale" (Moinet, 1981) was followed by a collective realisation of the importance of bocage, as recorded by Hubaud (1992): "when considering land development projects, efforts were made to limit hedge removal. During the 1970’s, in the Morbihan department, an average of 110 to 120 m of hedgerow per hectare was uprooted (and more than 200 m in certain locations). The figure has now fallen to 22 to 25 m."

Fortunately, a period of land consolidation marked by "hedge clearance on a massive scale" (Moinet, 1981) was followed by a collective realisation of the importance of bocage, as recorded by Hubaud (1992): "when considering land development projects, efforts were made to limit hedge removal. During the 1970’s, in the Morbihan department, an average of 110 to 120 m of hedgerow per hectare was uprooted (and more than 200 m in certain locations). The figure has now fallen to 22 to 25 m." Preserving the quality of bocage terrain for wildlife implies maintaining diversity in hedges, in terms of both their structure and their botanical composition, as well as preserving adjacent structures, ensuring that field sizes are appropriate and maintaining an unbroken hedge network.

Preserving the quality of bocage terrain for wildlife implies maintaining diversity in hedges, in terms of both their structure and their botanical composition, as well as preserving adjacent structures, ensuring that field sizes are appropriate and maintaining an unbroken hedge network.